Florida

A Reminiscence

My father was the last of eight kids. My mother was in the middle of six. My wife comes from a noticeably small family—she can count her cousins on her fingers. I had so many cousins growing up that it was difficult to remember all their names. There were dozens of them—some close but mostly scattered. My Christmases and calendars were filled with family and gatherings to celebrate. Birthday celebrations were enjoyable, especially once we moved to Florida.

There are some days you always remember. They are seared into our memories—indelible and, occasionally, scarring. These memories might be collective. They might be personal. They might be both. We hear people say they remember where they were and what they were doing when they heard about the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the assassination of President Kennedy or Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., or the moon landing. Those moments are locked in, trapping with them the sights, the sounds, and the actions haplessly accompanying those accidental moments. Moment and sensations unplanned but now paired in a sense-washed present. Years later, a similar smell or sound or image acts like a witch’s potion, reanimating that long-past day.

May 18, 1981, is one of those days for me. It is not the only day I remember with crisp clarity, yet it is one of those days that suggests how starkly different life was before compared with after. That day, it smelled like spring—freshly turned garden soil softened by a recent rain. Fragrant morning glories opening to the sun. Damp air lifting as that same sun burned off the dawn’s haze lingering in the deepest pockets of the valley, all the way up the cove.

It was our last day of spring on the top of the hill.

One year earlier, on the same day in May, Mount St. Helens erupted, catastrophically dislodging metric tons of tree, rock, and earth. The eruption permanently changed the shape of the landscape for dozens of miles in all directions. I remember sitting in front of the TV for hours, transfixed by the coverage of plumes of smoke and ash billowing into a pale blue sky. Little did I know, while watching in wonder at the Earth-shaping power beneath our feet, that a much smaller dislodging would reshape our lives the next year—a dislodging that was equally earthshaking for me. This dislodging was less eruption than disruption, removing not the top of a mountain but a family from a home on the top of a hill. The second May 18 temporarily ended my time in the Southern Uplands, marking the beginning of my family’s sojourn to Florida.

Just outside of Orlando, on a pencil-straight road heading toward St. Cloud, Grandma and Grandpa lived at the edge of a lake at the end of a trailer park. They owned the trailer park and lived in an “added-onto” wheeled home between the lake and their tenants. It was an exciting community and a fun summer place to explore.

A dozen trailers were primarily housing older folks who had lived on the tin-ringed oval. Many had become accustomed to seeing my brother and me on summer visits. That summer, we moved into a cracker shack in my grandparents’ backyard, a typical Florida midcentury bungalow tucked between their house and lake. Joining the trailers and the cracker shack were a couple of cinderblock houses, one of which housed my uncle and his family, and an odd collection of buildings and sheds. Those buildings kept my grandfather’s antique cars, a greenhouse, a workshop, and a mini sewage treatment plant. I was allowed inside them with permission. However, at the age of seven, the building I found most interesting was the worm house.

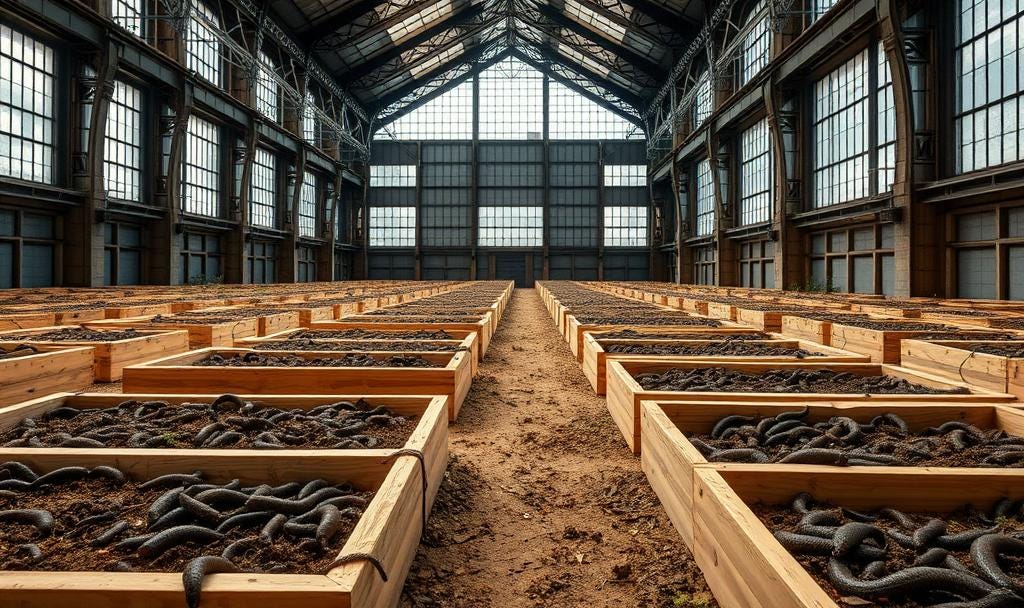

About the size of half a football field, the worm house was built to host nothing but thousands of night crawlers in beds of soil sitting about a yard above the ground. The building held dozens of these dirt tables lined up in an orderly grid with walking paths in between. Blanketed in the fog of time, I cannot remember if the tables still held live worms or just the memory of them when we arrived that summer. Regardless, in my seven-year-old imagination, the tables heaved and pulsated as the worms churned and turned the soil. The very promise of dancing dirt suspended three feet off the ground leaves an impression.

In Florida, we exchanged one set of cousins for another. My parents moved us to be closer to my mom’s family. Grandma and Grandpa had traveled a similar route years before, carrying their six kids from New Jersey to various cities in Florida, finally settling near Orlando. In the mountains, I had been one of the youngest cousins, having cousins who were adults well before I was even born. In Florida, my position was elevated: I went from the last grandson in the mountains to number two in the Sunshine State. Only my brother was ahead of me. When we moved to Florida, a few cousins might be counted besides my brother and me. Soon, we were joined by several more. I started collecting new Florida cousins at a steady pace. We even added one to the list when my sister was born later that first year. Our numbers got harder and harder to track. Grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins were close at hand. Adapting to multiplication, my grandparents decided that we would hold monthly birthday parties at their house on a given weekend each month to celebrate all the birthdays in that month. Practical and efficient, it was very much in keeping with a group populated by bookkeepers, engineers, and card counters.

From our gatherings by the lake for our monthly parties, I remember laughter, covered dishes, and sporadic arguments—arguments that often originated at the card table. No matter the occasion, gatherings at Grandma and Grandpa’s at some point centered around a card table. For the most part, playing cards was for the adults. Kids could play, but only if they played well and fast. Not knowing what to do next in gameplay or hesitating was discouraged…and often the source of the disagreements. If you could prove you could play well and quickly, you might be invited to squeeze in with the adults. I spent hours sitting on laps and watching, learning to count cards, cheat to see if anyone was noticing, and cussing.

Growing up, expletives were forbidden in my house—not even imagined. Around the card table, they were required, encouraged, and assumed. At least they were until the moment my two-year-old sister shouted out, “Damn it!” after failing to clear two pillows on the floor placed there for an impromptu broad jump. My mother had a “come-to-Jesus” meeting with her brothers. They behaved themselves for a few gatherings, but soon cursing became normative again. Every word imaginable—plus innovative combinations of them—filled the screened porch around card play well into the Florida nights.

Those nights by the lake had their own energy, joy, and damp lingering smells—the musky odor of condensation on vinyl and old outdoor carpet mixed with muck fires, a worm farm, and Grandpa’s cologne. They were not the smell of freshly turned soil touched by rain on a spring morning up a mountain cove. But they are the smell of unquestioned belonging and love.

Transported to 1981 with this.

💛